Children of Húrin essay by Adam Tolkien

12 Apr, 2007

(edited)

2007-4-12 5:33:56 PM UTC

2007-4-12 5:33:56 PM UTC

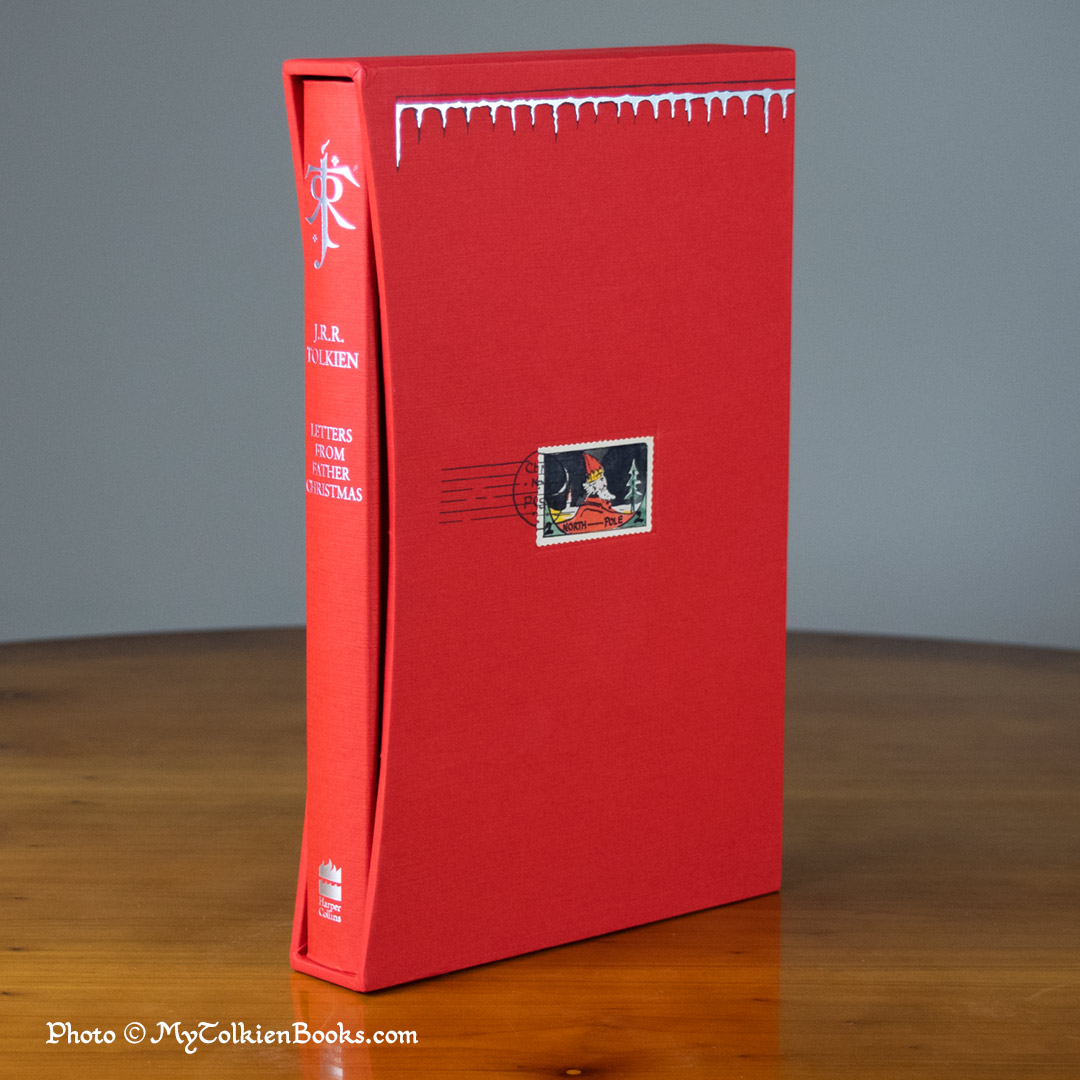

This was released by the publisher (Harper Collins in the UK):

THE CHILDREN OF HÚRIN by ADAM TOLKIEN

I was brought up in France, and although my grandfather died when I was very young, his work was always very much in evidence at home. My father, Christopher, the third of J.R.R. Tolkien's four children, according to his father's explicit wishes, has devoted himself to the publishing of my grandfather's massive archive of material ever since he began work on the "Silmarillion" papers in 1974. Ideally suited as he was through his twenty-five years of experience as a professor of Anglo-Saxon in Oxford, his work has always been that of the most rigorous editorial discipline. I have always been impressed by his ability to preserve his father's original writings as far as possible while applying the deft skill of an editor to make his volumes readable and not simply a catalogue of unpublished texts, something I was to learn first-hand when I undertook the daunting task of translating the first two volumes of The History of Middle-earth for Christian Bourgois, the French Tolkien publisher. With these books, complete with Christopher's notes, as well as being able to discover some otherwise completely unknown tales, readers could begin to understand the way the author worked, and see how he would write and rewrite, often revisiting the same stories and passages after many years, keen to refine and improve his vast mythology, as well as to accommodate into his earlier writing the fruits of his later invention and to create a complete and seamless mythology, a saga spanning thousands of years.

Having spent the three years immediately following J.R.R. Tolkien's death compiling The Silmarillion, Christopher went on to compile the book Unfinished Tales, followed by the 12-volume The History of Middle-earth, which was itself to take him 16 years. So when the twelfth volume, The Peoples of Middle-earth, was published in 1997, it seemed probable that this was to be Christopher's final book. The book's dedication to my mother, Baillie, did seem to make it clear that this was a conclusion to a long labour. But my father is as indefatigable as his father was, and he had been thinking for a long while of the possibility of a better and more complete version of one of the major tales from the Legendarium, "The Children of Húrin", and one that would be closer to his father's vision.

He has explained a little more extensively what had been his intention with The Children of Húrin :

`It is undeniable that there are a very great many readers of The Lord of the Rings for whom the legends of the Elder Days (as previously published in varying forms in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and The History of Middle-earth) are altogether unknown, unless by their repute as strange and inaccessible in mode and manner. For this reason it has seemed to me for a long time that there was a good case for presenting my father's long version of the legend of the Children of Húrin as an independent work, between its own covers, with a minimum of editorial presence, and above all in continuous narrative without gaps or interruptions, if this could be done without distortion or invention, despite the unfinished state in which he left some parts of it.

`When my father was a young man, during the years of the First World War and long before there was any inkling of the tales that were to form the narrative of The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, he began the writing of a collection of stories that he called The Book of Lost Tales. That was his first work of imaginative literature, and a substantial one, for though it was left unfinished there are fourteen completed tales. Among the Lost Tales three were of much greater length, and all three are concerned with Men as well as Elves: the stories of Beren and Lúthien, the Children of Húrin, and The Fall of Gondolin. In 1951, three years before the publication of The Fellowship of the Ring, he told of his early intention: "I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched."

`It thus seems unquestionable, from my father's own words, that if he could achieve final and finished narratives on the scale he desired, he saw the three "Great Tales" as works sufficiently complete in themselves as not to demand knowledge of the great body of legend known as The Silmarillion.'

Remarkably, considering that the earliest passages in The Children of Húrin are 90 years old, Christopher's reworking of the book works brilliantly. In a sense it is not a new book, for versions and pieces of the story will be familiar to some readers. For example, the whole tale was condensed down into a single chapter in The Silmarillion, as was the story of The Lord of the Rings at the end of that book, so what you have here is the reconstructed version, complete with familiar elements and also pieces that have never appeared before. (It might be compared to a sort of literary Director's Cut, the long version of the story assembled from all the best footage available, though my father probably wouldn't welcome the filmmaking comparison!)

We are especially delighted that HarperCollins agreed to publish the book with illustrations, and that the artist is Alan Lee (this was a particular request on Christopher's part). Alan was commissioned in 1990 to create the first-ever illustrated edition of The Lord of the Rings to mark Tolkien's Centenary, and his 50 watercolour paintings were to prove more influential than anyone could possibly have imagined, as Alan then spent five years in New Zealand working as conceptual designer with John Howe for the Peter Jackson trilogy. But now he is back, and has created some remarkable new paintings and pencil drawings for the book, while Christopher has himself redrawn the map, as indeed he did for The Lord of the Rings more than 50 years ago.

We hope that readers will be sufficiently attracted to the tragic tale of The Children of Húrin, and will discover the `great tale' that was so important to J.R.R. Tolkien and then the whole fascinating mythology that lies behind The Lord of the Rings. It is a testament to my father's skill as an editor that he has been able to construct a complete narrative without resorting to writing anything new. The words are one hundred percent J.R.R. Tolkien's, and for anyone who has read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, this book allows them to take a step back into a larger world, an ancient land of heroes and vagabonds, honour and jeopardy, hope and tragedy.

THE CHILDREN OF HÚRIN by ADAM TOLKIEN

I was brought up in France, and although my grandfather died when I was very young, his work was always very much in evidence at home. My father, Christopher, the third of J.R.R. Tolkien's four children, according to his father's explicit wishes, has devoted himself to the publishing of my grandfather's massive archive of material ever since he began work on the "Silmarillion" papers in 1974. Ideally suited as he was through his twenty-five years of experience as a professor of Anglo-Saxon in Oxford, his work has always been that of the most rigorous editorial discipline. I have always been impressed by his ability to preserve his father's original writings as far as possible while applying the deft skill of an editor to make his volumes readable and not simply a catalogue of unpublished texts, something I was to learn first-hand when I undertook the daunting task of translating the first two volumes of The History of Middle-earth for Christian Bourgois, the French Tolkien publisher. With these books, complete with Christopher's notes, as well as being able to discover some otherwise completely unknown tales, readers could begin to understand the way the author worked, and see how he would write and rewrite, often revisiting the same stories and passages after many years, keen to refine and improve his vast mythology, as well as to accommodate into his earlier writing the fruits of his later invention and to create a complete and seamless mythology, a saga spanning thousands of years.

Having spent the three years immediately following J.R.R. Tolkien's death compiling The Silmarillion, Christopher went on to compile the book Unfinished Tales, followed by the 12-volume The History of Middle-earth, which was itself to take him 16 years. So when the twelfth volume, The Peoples of Middle-earth, was published in 1997, it seemed probable that this was to be Christopher's final book. The book's dedication to my mother, Baillie, did seem to make it clear that this was a conclusion to a long labour. But my father is as indefatigable as his father was, and he had been thinking for a long while of the possibility of a better and more complete version of one of the major tales from the Legendarium, "The Children of Húrin", and one that would be closer to his father's vision.

He has explained a little more extensively what had been his intention with The Children of Húrin :

`It is undeniable that there are a very great many readers of The Lord of the Rings for whom the legends of the Elder Days (as previously published in varying forms in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and The History of Middle-earth) are altogether unknown, unless by their repute as strange and inaccessible in mode and manner. For this reason it has seemed to me for a long time that there was a good case for presenting my father's long version of the legend of the Children of Húrin as an independent work, between its own covers, with a minimum of editorial presence, and above all in continuous narrative without gaps or interruptions, if this could be done without distortion or invention, despite the unfinished state in which he left some parts of it.

`When my father was a young man, during the years of the First World War and long before there was any inkling of the tales that were to form the narrative of The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings, he began the writing of a collection of stories that he called The Book of Lost Tales. That was his first work of imaginative literature, and a substantial one, for though it was left unfinished there are fourteen completed tales. Among the Lost Tales three were of much greater length, and all three are concerned with Men as well as Elves: the stories of Beren and Lúthien, the Children of Húrin, and The Fall of Gondolin. In 1951, three years before the publication of The Fellowship of the Ring, he told of his early intention: "I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched."

`It thus seems unquestionable, from my father's own words, that if he could achieve final and finished narratives on the scale he desired, he saw the three "Great Tales" as works sufficiently complete in themselves as not to demand knowledge of the great body of legend known as The Silmarillion.'

Remarkably, considering that the earliest passages in The Children of Húrin are 90 years old, Christopher's reworking of the book works brilliantly. In a sense it is not a new book, for versions and pieces of the story will be familiar to some readers. For example, the whole tale was condensed down into a single chapter in The Silmarillion, as was the story of The Lord of the Rings at the end of that book, so what you have here is the reconstructed version, complete with familiar elements and also pieces that have never appeared before. (It might be compared to a sort of literary Director's Cut, the long version of the story assembled from all the best footage available, though my father probably wouldn't welcome the filmmaking comparison!)

We are especially delighted that HarperCollins agreed to publish the book with illustrations, and that the artist is Alan Lee (this was a particular request on Christopher's part). Alan was commissioned in 1990 to create the first-ever illustrated edition of The Lord of the Rings to mark Tolkien's Centenary, and his 50 watercolour paintings were to prove more influential than anyone could possibly have imagined, as Alan then spent five years in New Zealand working as conceptual designer with John Howe for the Peter Jackson trilogy. But now he is back, and has created some remarkable new paintings and pencil drawings for the book, while Christopher has himself redrawn the map, as indeed he did for The Lord of the Rings more than 50 years ago.

We hope that readers will be sufficiently attracted to the tragic tale of The Children of Húrin, and will discover the `great tale' that was so important to J.R.R. Tolkien and then the whole fascinating mythology that lies behind The Lord of the Rings. It is a testament to my father's skill as an editor that he has been able to construct a complete narrative without resorting to writing anything new. The words are one hundred percent J.R.R. Tolkien's, and for anyone who has read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, this book allows them to take a step back into a larger world, an ancient land of heroes and vagabonds, honour and jeopardy, hope and tragedy.

14

14 2814

2814